Confined Areas

(Updated on 5th April 2021)

What is a Confined Area?

Helicopters are designed to let us land in car parks, mountain tops, ships and any number of other unusual locations. For the purposes of this post, any area that is not an airport is considered a confined area. You may be landing in a 40 acre field – but if you do not follow a proper confined area procedure, there is an increased safety risk.

By learning the procedure for flying confined area approaches and take-offs, you will reduce the risk of anything going wrong by a substantial amount. This post will take you through the procedures for confined area operations.

This exercise is taught towards the end of your PPL training. The reason for this is that you need to be comfortable with flying the helicopter. This frees up your brain to think about other things. You need to be able to think ahead, plan ahead and anticipate what is coming up. You must be able to fly accurately. When you are relaxed and comfortable flying the helicopter, all of these things become easier to do.

Procedure

Once we learn a procedure then we ensure that we do the same things, in the correct order, each time. The procedure reduces the risk of us forgetting something. By using the procedure each time, then the confined area approach, landing, take-off and departure become safer.

The confined area LANDING procedure involves the following steps:

- Power check

- Reconnaissance

- Approach

- Landing

The confined area TAKE-OFF procedure involves the following steps:

- Power check

- Take-off

- Departure

Landing

Power Check

Before landing, it is vital that we perform a power check. We need to know if the helicopter can produce enough power to land or take-off safely. In my opinion, if you do not have enough power to hover (out of ground effect) then (as a low time pilot) you should not attempt to land in this area – instead, find an area where you can perform a normal approach to land.

The power check is described in detail in a previous post Power Checks.

Reconnaissance

The purpose of the reconnaissance is to let you survey the area where you are going to land. The reconnaissance will alert you to hazards, layout of the land, wind etc. This will also determine how you will do your approach. There are five main items to consider during the reconnaissance:

- Size

- Shape

- Surrounds

- Slope

- Surface

Fly the reconnaissance at 60kts (but no less than 50 knots) and 500 feet above ground level (AGL). A common mistake is to arrive at the area still doing 100 knots and this will severely reduce your time over the target and increase your workload. Fly around the area as many times as required.

If you are piloting from the right seat it is advisable to fly around the area in a clockwise direction as this makes it easier to see everything from your side window.

Size

Is the landing area physically large enough to do an approach and land the helicopter?

Shape

Is the shape suitable for making an approach? A narrow field that is parallel to the wind direction will be easy to make an approach to but if the same field has the wind blowing across it, then it may be inadvisable to land there.

Surrounds

Take a note of the surroundings. Some of the things to look for are:

- Trees on the approach and departure

- Buildings in the vicinity

- Animals – especially horses

- Electricity poles or pylons

- Cables

- Lead-in and lead-out markers

- Wind direction (described in wind direction)

It is important to choose a lead-in and lead-out marker. These are prominent and visible markers on the ground that you will be able to see from a long distance away. When you turn on final to land, you will be able to see these markers. When the markers are lined up, you will be able to fly a straight line to your landing site, even though the landing site may be in a valley and not visible at first until you get closer to it. The lead-in and lead-out markers should be pretty much pointing into wind and you must take this into account when choosing them.

When looking for animals, do not only look in the field where you are going to land. Look at the surrounding fields also. You should not attempt to land if there are horses nearby. Horses are easily spooked and some horses can be valued at more than your helicopter. You will have to use judgement when there are animals nearby.

Buildings and trees may require you to alter your approach path. Do not fly directly over the top of anyone’s house.

Cables are notoriously difficult to see. I have flown into areas where I know there are cables and I can see the poles supporting them. But under certain light conditions, these cables become invisible. They blend into the environment. Great care is needed. Look for the poles. Bear in mind that poles are often located in hedges and can be difficult to see. If you see poles, you should always assume that there are cables between them. As long as you can keep a safe distance between the helicopter and the cables, then there is no problem.

Slope

The slope should be continuously assessed during the approach. It will be difficult to see any degree of slope while you are flying at 500 feet. You will need a fairly level area to land on.

Surface

There are many different types of surface that we can land on. Some are listed below:

- Asphalt

- Concrete

- Gravel

- Short grass

- Long grass

- Ploughed

- Rocky

- Sand

- Snow

- Ice

- Wet or marshy land

Take into account the hazards associated with landing on each of these surfaces.

Approach

Once you have completed the reconnaissance, you can now fly to set yourself up for the approach. Keep flying at 60 knots and maintain approximately 500 feet AGL.

Fly as if you are flying a circuit pattern at an aerodrome. Set yourself up for a crosswind leg, a downwind leg and base leg before turning on final approach at 60 knots. Use the lead-in and lead-out markers to help you locate your turning point for final. If your helicopter is equipped with carburetor heat, it should be selected fully hot on the downwind leg.

Once you turn onto final approach, reduce your speed to 50 knots. Fly straight and level at 50 knots and 500 feet AGL until you see a sight picture for landing. Perform the approach and aim to pass at least 20 feet over any trees or obstacles close to the confined area. Keep an eye on the vertical speed indicator to avoid the risk of vortex ring developing.

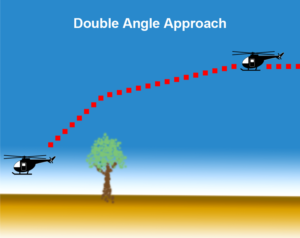

Double Angle Approach

Most confined area approaches will not permit you to fly a normal approach. Sometimes you will start off flying a normal approach but as you get closer, you will fly a steeper approach angle. This is called a double angle approach.

You may wish to fly a ‘Dummy’ approach to assess flight paths, reassess obstacles and hazards and to assess power requirements. This ‘Dummy’ approach will be terminated at a safe height and a climb to normal reconnaissance height will be made before performing the actual approach and landing.

At 300 feet AGL, start to reduce speed. Do not let the indicated airspeed go less than 30 knots until the rate of descent is less than 300 feet per minute.

At 200 feet AGL carburetor is selected fully cold and you must either commit to land or go-around.

At 100 feet AGL, ignore the sight picture and ensure the helicopter is moving forward and down. If you are passing over any tall objects, be aware that the tail rotor must also clear these obstacles.

Ensure that you keep at least 20 feet above any obstacles.

Choose a lateral marker in the landing area. This marker will normally be on your right hand side if you are sitting in the right seat. The purpose of this marker is to let you know when your tail rotor is clear of any obstacles. When the lateral marker is on your 3 o’clock position, it is safe to descend without the tail rotor coming into contact with any obstacles.

Landing

Come to a high hover (10 to 15 feet skid height). Perform a clearing turn to ensure that you are not landing on top of a concealed hazard or obstacle e.g. tree stumps, fence posts etc. It is a good idea to use a turn about the tail. This will ensure that the tail rotor does not move into an unseen object. But if you are not comfortable flying a turn while maintaining the tail over one spot, use sideways flight to clear the area before landing.

Use the sloped ground technique for landing.

If there is long grass, try to use the helicopter downwash to flatten it. This will help you see any rocks or tree stumps that may have been hidden.

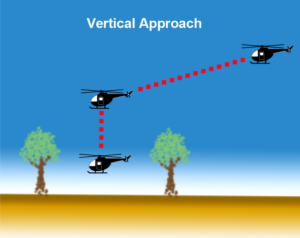

Vertical Descent

Some confined areas are so small that even a double angle approach is not practical. In this case you must aim to fly a normal approach that brings you directly overhead your landing area and then perform a vertical descent to the landing area. You will be flying inside the avoid curve for a a portion of this approach.

At 300 feet AGL, start to reduce speed. Do not let the indicated airspeed go less than 30 knots until the rate of descent is less than 300 feet per minute.

Use the tops of trees or obstacles (lined up with something further away) to keep a constant angle approach.

At 200 feet AGL carburetor is selected fully cold and you must either commit to land or go-around.

Fly the approach to come to a hover over the landing area. It is possible that you may be coming into a hover at 100 feet AGL or even higher. Make sure you have a lateral marker to alert you if you are moving forward or backwards. It is essential that you do not move forwards or backwards.

Smoothly descend and ensure that the rate of descent does not exceed 300 feet per minute (to avoid vortex ring state). Be aware that once you descend below any obstacle, you will lose the effect of the wind and the helicopter may start to descend faster, requiring more power to slow the rate of descent.

Come to a high hover (10 to 15 feet skid height) and perform a clearing turn before landing.

Use the sloped ground technique for landing.

Take-off

Power Check

Perform the take-off power check while in a low hover. Carburetor heat should be in the off position for the power check. If you do not have sufficient power available to perform a vertical climb out of ground effect, then consider reducing weight. This can be achieved by burning off some fuel or possibly asking a passenger to exit and arrange to pick him/her up in a nearby area where a normal take-off can be performed.

Take-off

Choose a heading and a lateral marker.

Ensure carburetor heat is fully cold and the engine temperatures and pressures are reading normal. Descend until the skids are close to the ground to get the maximum benefit from the ground cushion.

Smoothly raise the collective until the maximum manifold pressure is reached and climb vertically. Do not drift forward or backward. Only when you are above the level of the obstacles in front of you can you start to transition to forward flight. It is important to do this gently. You may get some extra lift from the wind (if there is any) when you clear the obstacles.

Departure

Smoothly accelerate to normal climb speed. Check the temperatures and pressures and make sure to visually check for other traffic in your area.

Practice

Initially, you will practice landing and taking off in relatively large areas but once you become comfortable flying in this environment, your instructor will get you to land in smaller and smaller areas. With practice, the procedure becomes second nature but you must always be aware that complacency can lead to serious mistakes.

As usual – if you can think of anything to add to this post or if you spot any errors, please let me know.

Did you enjoy this post? Why not leave a comment below and continue the conversation, or subscribe to my feed and get articles like this delivered automatically to your feed reader.

Comments

No comments yet.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.